Express Yourself Through Photography

Photography is about communication. When I started shooting pictures, it was to ease my sense of homesickness. It was the mid-1990s, a few years after I’d left my studies at St. Xavier University and followed my older brother from our home province of Nova Scotia to Toronto to pursue a career in music. (I’d begun playing the bass guitar at age 12.)

A lot had happened to me since leaving home. On August 12, 1991, while riding a mountain bike, I was struck by a tractor trailer. I ended up with a spinal cord injury, an above-the-hip amputation of my left leg, and a new existence to get used to. When I got out of the hospital two years later, I went back to playing and touring with bands. My life became a matter of logistics: How was I going to travel cross-country in a wheelchair, how was I going to get to the gigs, how would I get on and off the stage, and so on. These lessons and strategies would serve me well as a photographer in the years to come.

Music has always been my artistic outlet, and it continues to give me so much, even as the emphasis of my career moves away from performing and into teaching. I believe that art, like athletics, has the ability to enrich our lives in many ways. On my visits home to Halifax, I noticed that the city was changing due to development, and I wanted to preserve some of the landscapes that I felt helped define me.

I went to Henry’s on Church Street in Toronto and bought my first camera. In Halifax, I’d drive out to Lunenburg or Lawrencetown and take record shots of things I missed: the ocean, the coast, the Bluenose II. Being record shots, these negatives and slides almost all failed to capture what I was seeing in a way that a viewer would look and say “I get it.”

In 2001, I moved back to Halifax and married my college sweetheart, Pam. The focus of my life changed from survival to appreciating the beautiful things life has to offer. Photographers like Freeman Patterson showed me that “the camera points both ways.” Through the example of Freeman and impressionist artists like Alex Colville and Christopher Pratt, I started to explore a wider photographic world, the limits defined not by my physical ability but by my willingness to learn to see. If you’re willing to take a chance and open yourself to the possibilities, photography may inspire you, too.

A quick word about cameras: Any camera you can operate comfortably, with whatever disability you have, is the right one for you. Mine is a digital single-lens reflex (SLR) camera, which is a fancy way of saying that I can change the lens, and it uses memory cards instead of film.

For me, the ability to check my shots on the display screen on my camera is a great way to learn and advance as an artist. My home set-up includes a printer, so that I can control every aspect, from shooting to the final print. But if you use a disposable film camera and take it to the drugstore to be developed and that works for you, that’s all you need. Do whatever is right for your situation. Instead of taking pictures only to collect images, I started to shoot to express the sense of wonder and beauty I felt when looking at things around me.

Instead of shooting a whole boat, for example, I tried to capture the sense of stillness of the morning, the boat being a perfect reflection of this. I find that photography is an editing art – the choices I make aren’t only about what to shoot, but how to shoot.

The beautiful, sensual shape of the hull of a Cape Islander in Montague, P.E.I., sums up my admiration for its form (#3). By zooming in or out, getting closer or farther away, and selecting specific parts of the subject, I can say more about it than with a wider shot that shows everything. One mistake I made early in my photographic journey was thinking that the only good subjects were the ones I’d seen in magazines, such as exotic, faraway places. Photography isn’t about looking; it’s about seeing. I find that as I open my eyes and accept that there are great photos all around me, I become receptive to things I usually overlook.

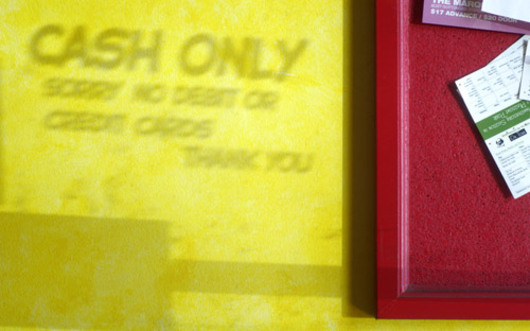

While dining with my wife and a friend at a restaurant called Tarek’s in Halifax, for example, I noticed how the words on the door seemed to be written on the wall via their shadow (#5). The things that attracted me were the great yellow wall, the red board and the way the shadow had real visual weight. Think of all the things like this that you pass every day. Many of the shots I take are at “chair level.” An able-bodied photographer once told me that it was too bad I can’t stand, so I could shoot the way he did. But I think my eye-line from the chair – or yours from a scooter or whatever your situation – can help make your photography a more personal expression, as long as you accept it as a gift and part of what makes you…well, you. Remember, you’re showing your world through your own eyes.

Part of learning to shoot involves how to hold the camera. My hands are unaffected by my disability. I use a tripod when the situation calls for it, and hand-hold at other times. If your hands shake, you could use a tripod to hold your camera still. Another option is to allow your shaking to become part of the image. One technique I use when shooting something moving, like flowers swaying in the wind (#9), is to express their movement with a longer exposure time. Adjusting my camera so that the shutter is open for part of a second, I “shake” the camera to give a sense of motion. This technique lends a more impressionistic air to a shot, and for me, it makes the photo more about my feelings for the flowers, rather than just a scientific record of them.

As well as the typical three-legged tripod, I’ve used my vehicle as a tripod. You can easily adapt a window-mounted spotting scope (such as one by Bushnell; see “Top Pix,” next page) to your needs. In a place where you’re unable to get out of your vehicle, you can attach the scope to your window and shoot away, which is what I did while in Grand Pre, N.S.

While taking a break after a long drive, I noticed the view of Blomidon. The sign blowing in the wind allowed me to see something I hadn’t considered: the human-made and natural landscapes together (#7). The shapes in the sign appear to “echo” the shape of the land behind it, which is a very lovely but over-photographed vista in Nova Scotia.

By being open to the possibility of an interesting photo, and not allowing the thought “What would a ‘real’ photographer do?” to stifle our creativity, we can create compelling, personal photographs that show as much about who we are inside as what we see on the outside.

The main reason I shoot is to capture my feelings about what’s going on in my life at any particular moment. My wife and I moved to P.E.I. in 2006. When we were picking up boxes at U-Haul in Dartmouth, I noticed the moving trailer next to me had Anne of Green Gables on the side, along with “U-Haul” in big letters (#8). All that remained was to rotate my camera to make Anne’s portrait square with the top edge and decide how much of the trailer to include to get my point across. There are things we pass every day that we take for granted.

A couple of days later, as we crossed on the ferry to our new home, I went onto the deck and took in the beautiful sunset. After taking a couple of record shots of the colours and thin sliver of moon, I adjusted my camera so that the shutter would be open for half a second. With some experimentation and patience, I made a shot that expresses my feeling of looking toward my future in my new home with my wife (#4). The effect is not of a sharp photograph, but of a painting. If I’d allowed myself to be affected by others’ expectations of what a photograph is supposed to be, I wouldn’t have a shot like this. I see a parallel between this and living with a disability: If I’d let myself be influenced by others’ expectations of what a person with a disability should be like, I wouldn’t have the life that I do.

One trend I’ve noticed in my portfolio is the inclusion of “damage” or “ugliness.” I put these in quotations because they’re subjective terms. For me, a rusty car is a whole other universe. Even something as common as a snow plow can make an interesting photo (#2). When looking at the well-used plow blade, I focus on its shape and texture, not what it “really is.”

One of the things my disability has taught me is that I create my own reality. Even when things seem bad, a sense of wonder and humour and an adventurous spirit can enrich anyone’s life. As an improvising musician, I love finding form in supposed chaos.

While shooting in a parking lot in Halifax, I noticed the reflection of graffiti on the side of a black car (#1). Looking at the wide view, it was just a car next to a wall. Looking through my camera and the tiny rectangle that is the viewfinder, I noticed that when I moved nearer, it appeared as if the car had been painted. By itself, that’s just an interesting picture. But then I saw a yellow bird in the corner of the window, looking at me and saying hello. For me, this is the real story of the photo. By taking a closer look at something, we can find the real meaning.