Mouth and Foot Painters Prove That No Obstacle Can Prevent True Expression

Susie Matthias holds a paintbrush in her mouth. She turns her head, dips the brush into paint, adjusts her head again and applies it to her canvas. While working on her latest painting of a woman in solitude by the Mexican sea, Matthias, 47, continues chatting—talking around the brush in her mouth.

Matthias, a thalidomide survivor, has been a mouth painter for close to 20 years. The boldly painted walls of her London, Ontario, condominium display replicas of many of her diverse works, which include paintings of a boy and his grandfather, a Rose of Sharon, a Victorian cottage, a pair of lions, a sunset and a butterfly.

Matthias was drawn to art from a young age. She took several courses but only began to take herself seriously as an artist after meeting the late mouth painter Myron Angus. He reviewed some of her work. “He was quite impressed,” recalls Matthias. Angus showed her how he held his brush at the end of a dowel, so that he wasn’t forced to lean in as far towards the canvas, but explained that she would have to come up with her own ideas about how to paint.

“Each mouth painter has their own technique,” says Matthias. “It’s what they feel most comfortable with in how to manipulate the paint brush.” Matthias began with watercolours and now paints mainly in oils. She especially enjoys painting places that mean something to her, as well as animals and landscapes.

And she’s not just painting for herself. Her work often appears on greeting cards and calendars for the Association of Mouth and Foot Painting Artists (MFPA) around the world. She presented “A Lady in Yellow,” her painting of the Victorian cottage, to David Onley, Ontario’s Lieutenant Governor. Onley also purchased her depiction of a polar bear to gift to Queen Elizabeth. A Matthias nativity scene was one of three Millennium Canada Post Christmas stamps painted by mouth artists. Recently, she also illustrated the cover of Kids of Courage, a children’s book tribute to Canada’s Paralympians.

Matthias credits her family, in particular her late parents, for their belief and encouragement. Her mother, unfortunately, passed away before Matthias had achieved her many successes. “My mother saw what I could be and my father saw what I had become,” she says. Her father was especially proud of the postage stamp.

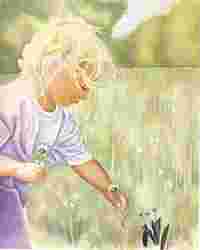

Her family is also a source of inspiration for her artwork. Her father and nephew are featured on one of the canvases that hangs on her wall, while the painting of her niece picking a flower in a field of daisies captures childhood innocence and delight.

“Susie is one of our most prolific artists. She’s fantastic,” says MFPA Canada director James Parkins. “Susie’s work is reproduced all over the world, from Australia to China to India. They love her work.”

Matthias is a member of the MFPA. The organization was established in Germany in 1956 by mouth painter Erich Stegmann, who survived polio. Stegmann brought “handless” artists together in a global enterprise to provide them independence by selling their work. There are now approximately 700 artists (13 in Canada) in 70 countries around the globe. The MFPA will celebrate their 50th anniversary in Canada next year.

The organization is a for-profit association owned and run by artists with disabilities. Members paint with brushes held in their mouths or feet, because disability prevents the use of their hands. There are three membership levels: student, associate and full. To apply, artists must submit samples of their work. Those accepted become student members. They receive a stipend for paint, materials, tuition or other expenses to help them on their journey to becoming more accomplished artists. After meeting standards, members can become associates, before being granted full membership.

It’s quite a process, but membership has its privileges. Full members receive lifelong incomes even if they are no longer able to paint because of health or other concerns.

The amount of income differs from artist to artist, depending on how much of their work has been produced. “The more you get produced, the more royalties you will get,” explains Parkins.

There are only three full members in Canada: Matthias, Cody Tresiera of British Columbia and Daniel LaFlamme of Quebec. Professional quality is essential. The MFPA generates revenue by publishing and selling cards, calendars, puzzles, wrapping paper and other items.

The organization holds an annual exhibition at its Toronto headquarters. Artists sometimes do demonstrations. Occasionally, workshops are offered at international conferences. Public reaction is very favourable. “The best thing is when [the artists] are there and they’re painting in front of people,” says Parkins. “[Audiences] cannot believe it.” In fact, the MFPA often receives calls of praise for the artists.

Scarborough, Ontario-based mouth artist Amanda Orichefsky appeared in a commercial with Wayne Gretzky for Ronald McDonald Children’s Charities when she was 13 years old. During the shoot, she tried to teach The Great One to paint with his mouth. Gretzky struggled. “I thought you were a better stick handler,” Orichefsky quipped. “So did I,” replied Gretzky. The ad became an instant classic.

After the commercial ran, the MFPA contacted Orichefsky and invited her to join as a student member. At 13, she was the youngest Canadian member. She still is today, at age 20. Orichefsky was born with arthrogryposis, a disorder that causes extreme restriction of her arms and legs. Around age five, she was “goofing around one day with colours and stuff” when she put a paintbrush in her mouth and showed her artistic flair. “Everything I do, and how I do it, I came up with myself,” she explains. “When I started painting, it was a way for me to have fun without relying on others.”

Orichefsky will soon complete the animation program at George Brown College. This fall, she will study graphic arts there. She enjoys doing pencil and ink work and also works with acrylic, watercolours and Indian ink. She does computer art using her chin on the mouse and uses the keyboard with a pen in her mouth.

The young artist’s work has been displayed at MFPA exhibitions but hasn’t shown up on cards or calendars…yet. She hopes it will someday, as she aspires to become an associate or full MFPA member.

Mouth painting has been around for a long time. The first documented mouth painter was Sarah Biffen (1784-1850), a British artist without arms or legs. During her adult life, Biffen made her living travelling with a sideshow. Yet, her talent was so great that one of her paintings was accepted by London’s Royal Academy.

But there’s an “F” in MFPA, too. Though foot painting is not as common as mouth painting, perhaps the best-known foot painter was Christy Brown, author of the book My Left Foot, which was later made into a movie. When the Irish painter, who had cerebral palsy, was in his early 20s, Stegmann travelled to Dublin to meet with him. There, he invited Brown to become a member of the association. This ended much of Brown’s isolation, provided him financial independence and helped him to become a recognized artist around the world.

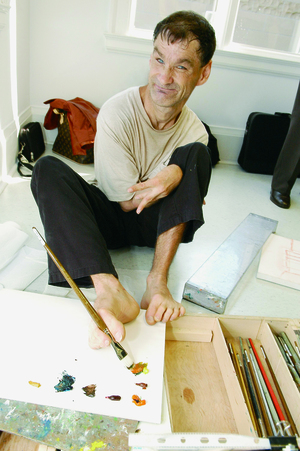

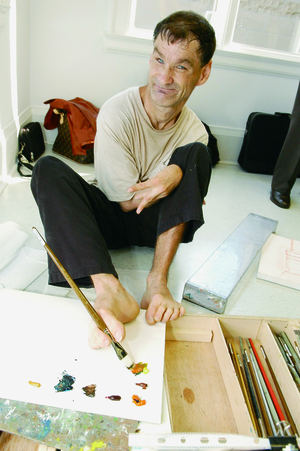

Daniel LaFlamme is Canada’s only MFPA foot painter. Like Brown, LaFlamme has cerebral palsy. After seeing a telecast about a young girl without arms using her feet to perform many tasks, LaFlamme swiftly learned to eat and draw with his feet. At age 24, staff of a rehabilitation centre registered him for painting classes. It wasn’t long before his talent was recognized.

The Quebec-based artist joined the MFPA in 1985 and his first work was reproduced on a card that same year. LaFlamme takes his inspiration for his landscapes and other oil paintings mainly from the scenic Quebec countryside. In addition to independence, LaFlamme says that art gives him “a reason to live.”

The work of MFPA artists is as varied as the individuals themselves. But, the artists share a common desire. “They want to be respected for art that is just as good as able-bodied artists,” says Parkins. Those who have had the privilege of viewing their artwork, including Queen Elizabeth herself, will no doubt agree that it is.

By Lynne Swanson